|

| Kermode or Spirit Bear, Ursus americanus kermodei |

Sunday, March 31, 2024

CANADA'S GREAT BEARS

Saturday, March 30, 2024

ARMOURED ANIMALS: ANCIENT ARMADILLOS

Glyptodonts became extinct at the end of the last ice age. They, along with a large number of other megafaunal species, including pampatheres, the giant ground sloths, and the Macrauchenia, left this Earth but their bones tell a story of brief and awesome supremacy.

Today, Glyptodonts live on through their much smaller, more lightly armoured and flexible armadillo relatives. They defended themselves against Sabre Tooth Cats and other predators but could not withstand the arrival of early humans in the Americas. Archaeological evidence suggests that these humans made use of the animal's armoured shells and enjoyed the meat therein. Glyptodonts possessed a tortoise-like body armour, made of bony deposits in their skin called osteoderms or scutes. Beneath that hard outer coating was a food source that our ancestors sought for their survival.

Each species of glyptodont had a unique osteoderm pattern and shell type. With this protection, they were armoured like turtles; glyptodonts could not withdraw their heads, but their armoured skin formed a bony cap on the top of their skull. Glyptodont tails had a ring of bones for protection. Doedicurus possessed a large mace-like spiked tail that it would have used to defend itself against predators and, possibly, other Doedicurus. Glyptodonts had the advantage of large size.

Many, such as the type genus, Glyptodon, were the size of modern automobiles. The presence of such heavy defences suggests they were the prey of a large, effective predator. At the time that glyptodonts evolved, the apex predators in the island continent of South America were phorusrhacids, a family of giant flightless carnivorous birds.

|

| The ancient Armadillo Glyptodon asper |

These are examples of the convergent evolution of unrelated lineages into similar forms. The largest glyptodonts could weigh up to 2,000 kilograms. Like most of the megafauna in the Americas, they all became extinct at the end of the last ice age 10,000 years ago. The deeper you get in time, the larger they were. Twenty thousand years ago, they could have ambled up beside you in what would become Argentina and outweighed a small car.

A few years back, some farmers found some interesting remains in a dried-out riverbed near Buenos Aires. The find generated a ton of palaeontological excitement. Fieldwork revealed this site to contain two adults and two younger specimens of an ancient armadillo. These car-size beasties would have been living and defending themselves against predators like Sabre Tooth Cats and other large predators of the time by employing their spiked club-like tails and thick bony armour.

Glyptodonts were unlikely warriors. They were grazing herbivores. Like many other xenarthrans, they had no incisor or canine teeth but had a number of cheek teeth that would have been able to grind up tough vegetation, such as grasses. They also had distinctively deep jaws, with large downward bony projections that would have anchored their powerful chewing muscle.

Image Two: By Arentderivative work: WolfmanSF (talk) - http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bild:Glyptodon-1.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=665483

Friday, March 29, 2024

AMYLASE: YOU ARE WHAT YOU EAT

|

For all the mammals, you and I included, we need the amylase gene (AMY). It codes for a starch-digesting enzyme needed to break down the vegetation we eat.

Humans, dogs and mice have record numbers of the amylase gene. The AMY gene copy number increases in mammal populations where starch-based foods are more abundant. Think toast and jam versus raw chicken.

A good example of this is seen when we compare wolves living in the wild to dogs from agricultural societies. Dogs split off the lineage from wolves around 30,000–40,000 years ago.

Domesticated dogs have extra copies of amylase and other genes involved in starch digestion that contribute to an increased ability to thrive on a starch-rich diet, allowing Fido to make the most of those table scraps. Similar to humans, some dog breeds produce amylase in their saliva, a clear marker of a high starch diet. So do mice, rats, and pigs, as expected as they live in concert with humans. Curiously, so do some New World monkeys, boars, deer mice, woodrats, and giant African pouched rats.

More like cats and less like other omnivores, dogs can only produce bile acid with taurine and they cannot produce vitamin D, which they obtain from animal flesh. Also, more like cats, dogs require arginine to maintain their nitrogen balance. These nutritional requirements place dogs halfway between carnivores and omnivores.

The amount of AMY and starch in the diet varies among subspecies, and sometimes even amongst geographically distinct populations of the same species. I was at a talk recently given by Alaskan wolf researchers who shared that two individual packs of wolves separated by less than a kilometre ate vastly different diets. This had me thinking about what we eat and it is mostly driven by what is on offer.

Diet impacts our genetics and this, in turn, allows the fittest to eat, digest and survive. While wolves win the carnivore contest, they will still eat opportunistically and that includes vegetation when other food is scarce. Would they evolve similar levels of AMY as humans, dogs and mice? Maybe if their diets evolved to be similar. Likely. The choice would be that or starvation.

The evolution of amylase in other domesticated or human commensal mammals remains an alluring area of inquiry.

Reference:

Amylase in Dietary Food Preferences in Mammals: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6516957/

Tuesday, March 26, 2024

PARASAUROLOPHUS WALKERI OF ALBERTA

|

| Holotype Specimen of P. walkeri, Royal Ontario Museum |

Monday, March 25, 2024

DESMOCERAS OF MAHAJANGA

Ammonites were predatory, squid-like creatures that lived inside coil-shaped shells. Like other cephalopods, ammonites had sharp, beak-like jaws inside a ring of squid-like tentacles.

They used their tentacles to snare prey, — plankton, vegetation, fish and crustaceans — similar to the way a squid or octopus hunt today.

Sunday, March 24, 2024

STUPENDEMYS GEOGRAPHICUS: A COLOSSAL TURTLE

These aquatic beasties had shells almost three metres long (up to 9.5 feet) making it about a 100 times larger and sharing mixed traits with some of it's nearest living relatives — the giant South American River Turtle, Podocnemis expansa and Yellow-Spotted Amazon River Turtle, Podocnemis unifilis, the Amazon river turtle, Peltocephalus dumerilianus, and twice that of the largest marine turtle, the leatherback, Dermochelys coriacea.

It was also larger than those huge Archelon turtles that lumbered along during the Late Cretaceous at a whopping 15 feet, just over 4.5 metres. Stupendemys geographicus lived during the Miocene in Venezuela and Columbia. South America is a treasure trove of unique fossil fauna.

Throughout its history, the region has been home to giant rodents and an amazing assortment of crocodylians. It was also home to one of the largest turtles that ever lived. But for many years, the biology and systematics of Stupendemys geographicus remained largely unknown. When we found them in the fossil record it is usually as bits and pieces of shell and bone; exciting finds but not enough for us to see the big picture.

|

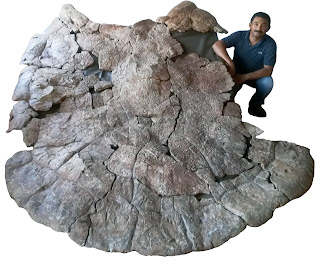

| Palaeontologist Rodolfo Sánchez with Stupendemys geographicus |

But for almost four decades, very few complete carapaces or other telltale fossils of Stupendemys were found in the region.

This excited Edwin Cadena, Paleontologist at the Universidad del Rosario in Colombia and researchers of the University of Zurich (UZH) and fellow researchers from Colombia, Venezuela, and Brazil. They had very good reason to believe that it was just a matter of time before more complete specimens were to be found. The area is a wonderful place to do fieldwork. It's an arid, desert locality without plant or forest coverage we see at other sites. Fossils weather out but do not wash away like they do at other sites.

Their efforts paid off and the fossils are marvellous. Shown here is Venezuelan Palaeontologist Rodolfo Sánchez with a male carapace (showing the horns) of Stupendemys geographical. This is one of the 8 million-year-old specimens from Venezuela.

|

| Rodolfo Sánchez with Stupendemys geographicus |

Together, they paint a much clearer picture of a large terrestrial turtle that varied its diet and had distinct differences between the males and females in their morphology. Cadena published in February of this year with his colleagues in the journal Science Advances.

The researchers grouped together from multiple sites to help create a better understanding of the biology, lifestyle and phylogenetic position of these gigantic neotropical turtles.

Their paper includes the reporting of the largest carapace ever recovered and argues for a sole giant erymnochelyin taxon, S. geographicus, with extensive geographical distribution in what was the Pebas and Acre systems — pan-Amazonia during the middle Miocene to late Miocene in northern South America).

This turtle was quite the beast with two lance-like horns and battle scars to show it could hold its own with the apex predators of the day.

They also hypothesize that S. geographicus exhibited sexual dimorphism in shell morphology, with horns in males and hornless females. From the carapace length of 2.40 metres, they estimate to total mass of these turtles to be up to 1.145 kg, almost 100 times the size of its closest living relative. The newly found fossil specimens greatly expand the size of these fellows and our understanding of their biology and place in the geologic record.

Their conclusions paint a picture of a single giant turtle species across the northern Neotropics, but with two shell morphotypes, further evidence of sexual dimorphism. These were tuff turtles to prey upon. Bite marks and punctured bones tell us that they faired well from what must have been frequent predatory interactions with large, 30 foot long (over 9 metres) Caimans — big, burly alligatorid crocodilians — that also inhabited the northern Neotropics and shared their roaming grounds. Even with their large size, they were a very tempting snack for these brutes but unrequited as it appears Stupendemys fought, won and lumbered away.

Image Two: Venezuelan Palaeontologist Rodolfo Sánchez and a male carapace of Stupendemys geographicus, from Venezuela, found in 8 million years old deposits. Photo credit: Jorge Carrillo

Image Three: Venezuelan Palaeontologist Rodolfo Sánchez and a male carapace of Stupendemys geographicus, from Venezuela, found in 8 million years old deposits. Photo credit: Edwin Cadena

Reference: E-A. Cadena, T. M. Scheyer, J. D. Carrillo-Briceño, R. Sánchez, O. A Aguilera-Socorro, A. Vanegas, M. Pardo, D. M. Hansen, M. R. Sánchez-Villagra. The anatomy, paleobiology and evolutionary relationships of the largest side-necked extinct turtle. Science Advances. 12 February 2020. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aay4593

Saturday, March 23, 2024

TEMPERATURE, SAND AND SEX: GREEN SEA TURTLES

It is the only species in the genus Chelonia. Its range extends throughout tropical and subtropical seas around the world, with two distinct populations in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, but it is also found in the Indian Ocean.

This sea turtle's dorsoventrally flattened body is covered by a large, teardrop-shaped carapace; it has a pair of large, paddle-like flippers. It is usually lightly coloured, although in the eastern Pacific populations' parts of the carapace can be almost black. Unlike other members of its family, such as the hawksbill sea turtle, C. mydas is mostly herbivorous. The adults usually inhabit shallow lagoons, feeding mostly on various species of seagrasses. The turtles bite off the tips of the blades of seagrass, which keeps the grass healthy and these aquatic vegans in top shape..

Like other sea turtles, green sea turtles migrate long distances between feeding grounds and hatching beaches. Many islands worldwide are known as Turtle Island due to green sea turtles nesting on their beaches. Females crawl out on beaches, dig nests and lay eggs during the night. Later, hatchlings emerge and scramble into the water. Those that reach maturity may live to 80 years in the wild.

Researchers at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Frankfurt, Germany discovered the remains of the oldest fossilized sea turtle known to date. Remains from a new species, Desmatochelys padillai sp, including fossilized shell and bones have been found at two outcrops near Villa de Leyva, Colombia.

Friday, March 22, 2024

MIGHTY EAGLE: KWIKW (KW-EE-KW)

|

| Bald Eagle / Kwikw / Haliaeetus leucocephalus |

Thursday, March 21, 2024

FRACTAL BUILDING: AMMONITES

|

| Argonauticeras besairei, Collection of José Juárez Ruiz. |

Ammonites were predatory, squid-like creatures that lived inside coil-shaped shells.

Like other cephalopods, ammonites had sharp, beak-like jaws inside a ring of squid-like tentacles that extended from their shells. They used these tentacles to snare prey, — plankton, vegetation, fish and crustaceans — similar to the way a squid or octopus hunt today.

Catching a fish with your hands is no easy feat, as I'm sure you know. But the Ammonites were skilled and successful hunters. They caught their prey while swimming and floating in the water column. Within their shells, they had a number of chambers, called septa, filled with gas or fluid that were interconnected by a wee air tube. By pushing air in or out, they were able to control their buoyancy in the water column.

They lived in the last chamber of their shells, continuously building new shell material as they grew. As each new chamber was added, the squid-like body of the ammonite would move down to occupy the final outside chamber.

They were a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids — octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish) than they are to shelled nautiloids such as the living Nautilus species.

The Ammonoidea can be divided into six orders:

- Agoniatitida, Lower Devonian - Middle Devonian

- Clymeniida, Upper Devonian

- Goniatitida, Middle Devonian - Upper Permian

- Prolecanitida, Upper Devonian - Upper Triassic

- Ceratitida, Upper Permian - Upper Triassic

- Ammonitida, Lower Jurassic - Upper Cretaceous

If they are ceratitic with lobes that have subdivided tips; giving them a saw-toothed appearance and rounded undivided saddles, they are likely Triassic. For some lovely Triassic ammonites, take a look at the specimens that come out of Hallstatt, Austria and from the outcrops in the Humboldt Mountains of Nevada.

|

| Hoplites bennettiana (Sowby, 1826). |

One of my favourite Cretaceous ammonites is the ammonite, Hoplites bennettiana (Sowby, 1826). This beauty is from Albian deposits near Carrière de Courcelles, Villemoyenne, near la région de Troyes (Aube) Champagne in northeastern France.

At the time that this fellow was swimming in our oceans, ankylosaurs were strolling about Mongolia and stomping through the foliage in Utah, Kansas and Texas. Bony fish were swimming over what would become the strata making up Canada, the Czech Republic and Australia. Cartilaginous fish were prowling the western interior seaway of North America and a strange extinct herbivorous mammal, Eobaatar, was snuffling through Mongolia, Spain and England.

In some classifications, these are left as suborders, included in only three orders: Goniatitida, Ceratitida, and Ammonitida. Once you get to know them, ammonites in their various shapes and suturing patterns make it much easier to date an ammonite and the rock formation where is was found at a glance.

Ammonites first appeared about 240 million years ago, though they descended from straight-shelled cephalopods called bacrites that date back to the Devonian, about 415 million years ago, and the last species vanished in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

They were prolific breeders that evolved rapidly. If you could cast a fishing line into our ancient seas, it is likely that you would hook an ammonite, not a fish. They were prolific back in the day, living (and sometimes dying) in schools in oceans around the globe. We find ammonite fossils (and plenty of them) in sedimentary rock from all over the world.

In some cases, we find rock beds where we can see evidence of a new species that evolved, lived and died out in such a short time span that we can walk through time, following the course of evolution using ammonites as a window into the past.

For this reason, they make excellent index fossils. An index fossil is a species that allows us to link a particular rock formation, layered in time with a particular species or genus found there. Generally, deeper is older, so we use the sedimentary layers rock to match up to specific geologic time periods, rather the way we use tree-rings to date trees. A handy way to compare fossils and date strata across the globe.

https://www.nature.com/articles/srep33689?fbclid=IwAR1BhBrDqhv8LDjqF60EXdfLR7wPE4zDivwGORTUEgCd2GghD5W7KOfg6Co#citeas

Photo: Hoplites Bennettiana from near Troyes, France. Collection de Christophe Marot

Wednesday, March 20, 2024

SHELL MIDDENS: CaCO3 + CO2 + H2O → Ca (HCO3)2

This past weekend, I was exploring the western edge of central Vancouver Island, home to the Pacheedaht First Nation. Their traditional unceded territory is wonderous.

The beaches are covered with bits of fir, cedar and arbutus worn smooth by the awesome west coast waves! I can see why they have made a home here for millennia.

Those of you who live near the sea understand the compulsion to collect driftwood, unusual stones, fossils—and shells. They add a little something to our homes and gardens.

With a strong love of natural objects, my own home boasts several stunning abalone shells conscripted into service as both spice dish, soap dish and the place I both store and display beautiful bits from nature.

As well as beautiful debris, shells also played an embalming role as they collect in shell middens from coastal communities. Having food “packaging” accumulate in vast heaps around towns and villages is hardly a modern phenomenon.

Many First Nations sites were inhabited continually for centuries. The discarded shells and scraps of bone from their food formed enormous mounds, called middens. Left over time, these unwanted dinner scraps transform through a quiet process of preservation.

Time and pressure leach the calcium carbonate, CaCO3, from the surrounding marine shells and help “embalm” bone and antler artifacts that would otherwise decay. Useful this, as antler makes for a fine sewing tool when worked into a needle. Much of what we know around the modification of natural objects into tools comes from this preservation.

|

| Comox Beach, Kʼómoks First Nation / Photo: Kat Frank |

In prepping fossil specimens embedded in limestone, it is useful to know that it reacts with stronger acids, releasing carbon dioxide: CaCO3(s) + 2HCl(aq) → CaCl2(aq) + CO2(g) + H2O(l)

For those of you wildly interested in the properties of CaCO3, may also find it interesting to note that calcium carbonate also releases carbon dioxide on when heated to greater than 840°C, to form calcium oxide or quicklime, reaction enthalpy 178 kJ / mole: CaCO3 → CaO + CO2.

Calcium carbonate reacts with water saturated with carbon dioxide to form the soluble calcium bicarbonate. Bone already contains calcium carbonate, as well as calcium phosphate, Ca2, but it is also made of protein, cells and living tissue.

Decaying bone acts as a sort of natural sponge that wicks in the calcium carbonate displaced from the shells. As protein decays inside the bone, it is replaced by the incoming calcium carbonate, making makes the bone harder and more durable.

The shells, beautiful in their own right, make the surrounding soil more alkaline, helping to preserve the bone and turning the dinner scraps into exquisite scientific specimens for future generations.

The lovely photo from Comox showing the many shells on the beach is by my beautiful cousin Kat Frank of the Kʼómoks First Nation—an amazing human being and, as you can see, a great photographer!

Tuesday, March 19, 2024

NOOTKA: FOSSILS AND FIRST NATION HISTORY

.jpg) |

| Nootka Fossil Field Trip. Photo: John Fam |

Just off the shores of Vancouver Island, east of Gold River and south of Tahsis is the picturesque and remote Nootka Island.

This is the land of the proud and thriving Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations who have lived here always.

Always is a long time, but we know from oral history and archaeological evidence that the Mowachaht and Muchalaht peoples lived here, along with many others, for many thousands of years — a time span much like always.

While we know this area as Nootka Sound and the land we explore for fossils as Nootka Island, these names stem from a wee misunderstanding.

Just four years after the 1774 visit by Spanish explorer Juan Pérez — and only a year before the Spanish established a military and fur trading post on the site of Yuquot — the Nuu-chah-nulth met the Englishman, James Cook.

Captain Cook sailed to the village of Yuquot just west of Vancouver Island to a very warm welcome. He and his crew stayed on for a month of storytelling, trading and ship repairs. Friendly, but not familiar with the local language, he misunderstood the name for both the people and land to be Nootka. In actual fact, Nootka means, go around, go around.

Two hundred years later, in 1978, the Nuu-chah-nulth chose the collective term Nuu-chah-nulth — nuučaan̓uł, meaning all along the mountains and sea or along the outside (of Vancouver Island) — to describe themselves.It is a term now used to describe several First Nations people living along western Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

It is similar in a way to the use of the United Kingdom to refer to the lands of England, Scotland and Wales — though using United Kingdom-ers would be odd. Bless the Nuu-chah-nulth for their grace in choosing this collective name.

An older term for this group of peoples was Aht, which means people in their language and is a component in all the names of their subgroups, and of some locations — Yuquot, Mowachaht, Kyuquot, Opitsaht. While collectively, they are the Nuu-chah-nulth, be interested in their more regional name should you meet them.

But why does it matter? If you have ever mistakenly referred to someone from New Zealand as an Aussie or someone from Scotland as English, you have likely been schooled by an immediate — sometimes forceful, sometimes gracious — correction of your ways. The best answer to why it matters is because it matters.

Each of the subgroups of the Nuu-chah-nulth viewed their lands and seasonal migration within them (though not outside of them) from a viewpoint of inside and outside. Kla'a or outside is the term for their coastal environment and hilstis for their inside or inland environment.

It is to their kla'a that I was most keen to explore. Here, the lovely Late Eocene and Early Miocene exposures offer up fossil crab, mostly the species Raninid, along with fossil gastropods, bivalves, pine cones and spectacularly — a singular seed pod. These wonderfully preserved specimens are found in concretion along the foreshore where time and tide erode them out each year.

Five years after Spanish explorer Juan Pérez's first visit, the Spanish built and maintained a military post at Yuquot where they tore down the local houses to build their own structures and set up what would become a significant fur trade port for the Northwest Coast — with the local Chief Maquinna's blessing and his warriors acting as middlemen to other First Nations.

Following reports of Cook's exploration British traders began to use the harbour of Nootka (Friendly Cove) as a base for a promising trade with China in sea-otter pelts but became embroiled with the Spanish who claimed (albeit erroneously) sovereignty over the Pacific Ocean.

|

| Dan Bowen searching an outcrop. Photo: John Fam |

George Vancouver on his subsequent exploration in 1792 circumnavigated the island and charted much of the coastline. His meeting with the Spanish captain Bodega y Quadra at Nootka was friendly but did not accomplish the expected formal ceding of land by the Spanish to the British.

It resulted however in his vain naming the island "Vancouver and Quadra." The Spanish captain's name was later dropped and given to the island on the east side of Discovery Strait. Again, another vain and unearned title that persists to this day.

Early settlement of the island was carried out mainly under the sponsorship of the Hudson's Bay Company whose lease from the Crown amounted to 7 shillings per year — that's roughly equal to £100.00 or $174 CDN today. Victoria, the capital of British Columbia, was founded in 1843 as Fort Victoria on the southern end of Vancouver Island by the Hudson's Bay Company's Chief Factor, Sir James Douglas.

With Douglas's help, the Hudson's Bay Company established Fort Rupert on the north end of Vancouver Island in 1849. Both became centres of fur trade and trade between First Nations and solidified the Hudson's Bay Company's trading monopoly in the Pacific Northwest.The settlement of Fort Victoria on the southern tip of Vancouver Island — handily south of the 49th parallel — greatly aided British negotiators to retain all of the islands when a line was finally set to mark the northern boundary of the United States with the signing of the Oregon Boundary Treaty of 1846. Vancouver Island became a separate British colony in 1858. British Columbia, exclusive of the island, was made a colony in 1858 and in 1866 the two colonies were joined into one — becoming a province of Canada in 1871 with Victoria as the capital.

Dan Bowen, Chair of the Vancouver Island Palaeontological Society (VIPS) did a truly splendid talk on the Fossils of Nootka Sound. With his permission, I have uploaded the talk to the ARCHEA YouTube Channel for all to enjoy. Do take a boo, he is a great presenter. Dan also graciously provided the photos you see here. The last of the photos you see here is from the August 2021 Nootka Fossil Field Trip. Photo: John Fam, Vice-Chair, Vancouver Paleontological Society (VanPS).

Know Before You Go — Nootka Trail

The Nootka Trail passes through the traditional lands of the Mowachaht/Muchalat First Nations who have lived here since always. They share this area with humpback and Gray whales, orcas, seals, sea lions, black bears, wolves, cougars, eagles, ravens, sea birds, river otters, insects and the many colourful intertidal creatures that you'll want to photograph.

This is a remote West Coast wilderness experience. Getting to Nootka Island requires some planning as you'll need to take a seaplane or water taxi to reach the trailhead. The trail takes 4-8 days to cover the 37 km year-round hike. The peak season is July to September. Permits are not required for the hike.

Access via: Air Nootka floatplane, water taxi, or MV Uchuck III

- Dan Bowen, VIPS on the Fossils of Nootka: https://youtu.be/rsewBFztxSY

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sir-james-douglas

- file:///C:/Users/tosca/Downloads/186162-Article%20Text-199217-1-10-20151106.pdf

- Nootka Trip Planning: https://mbguiding.ca/nootka-trail-nootka-island/#overview

Monday, March 18, 2024

JAPANESE CORKSCREW AMMONITE: HYPHANTOCERAS ORIENTALE

This an adult specimen (not the juvenile stage) from Upper Santonian outcrops near Ashibetsu, Hokkaido, Japan.

Aiba published on a possible phylogenetic relationship of two species of Hyphantoceras (Ammonoidea, Nostoceratidae) earlier this year, proposing that a phylogenetic relationship may exist based on newly found specimens with precise stratigraphic occurrences in the Kotanbetsu and Obira areas, northwestern Hokkaido.

Two closely related species, Hyphantoceras transitorium and H. orientale, were recognized in the examined specimens from the Kotanbetsu and Obira areas. Specimens of H. transitorium show wide intraspecific variation in the whorl shape. The stratigraphic occurrences of the two species indicate that they occur successively in the Santonian–lowermost Campanian, without stratigraphic overlapping.

Aiba, Daisuke. (2019). A Possible Phylogenetic Relationship of Two Species of Hyphantoceras (Ammonoidea, Nostoceratidae) in the Cretaceous Yezo Group, Northern Japan. Paleontological Research. 23. 65-80. 10.2517/2018PR010.

Saturday, March 16, 2024

DRIFTWOOD CANYON FOSSIL BEDS / KUNGAX

|

| Puffbird similar to Fossil Birds found at Driftwood Canyon |

|

| Metasequoia, the Dawn Redwood |

|

| A Tapir showing off his prehensile nose trunk |

Tuesday, March 5, 2024

MEET FERGUSONITES HENDERSONAE: HETTANGIAN AMMONITE

|

| Fergusonites hendersonae (Longridge, 2008) |

I had the very great honour of having this fellow, a new species of nektonic carnivorous ammonite, named after me by paleontologist Louse Longridge from the University of British Columbia. I'd met Louise as an undergrad and was pleased as punch to hear that she would be continuing the research by Dr. Howard Tipper.

We did several trips over the years up to the Taseko Lake area of the Rockies joined by many wonderful researchers from Vancouver Island Palaeontological Society and Vancouver Paleontological Society, as well as the University of British Columbia. Both Dan Bowen and John Fam were instrumental in planning those expeditions. We endured elevation sickness, rain, snow, grizzly bears and very chilly nights (we were sleeping right next to a glacier at one point) but were rewarded by the enthusiastic crew, helicopter rides (which really cut down the hiking time) excellent specimens and stunningly beautiful country. We were also blessed with excellent access as the area is closed to collecting except with a permit.

Reference: PaleoDB 157367 M. Clapham GSC C-208992, Section A 09, Castle Pass Angulata - Jurassic 1 - Canada, Longridge et al. (2008)

Full reference: L. M. Longridge, P. L. Smith, and H. W. Tipper. 2008. Late Hettangian (Early Jurassic) ammonites from Taseko Lakes, British Columbia, Canada. Palaeontology 51:367-404

PaleoDB taxon number: 297415; Cephalopoda - Ammonoidea - Juraphyllitidae; Fergusonites hendersonae Longridge et al. 2008 (ammonite); Average measurements (in mm): shell width 9.88, shell diameter 28.2; Age range: 201.6 to 196.5 Ma. Locality info: British Columbia, Canada (51.1° N, 123.0° W: paleo coordinates 22.1° N, 66.1° W)

LOTUS FLOWER FRUIT

|

| Lotus Flower Fruit, Nelumbo |

The awesome possums from GRS are based out of North Logan, Utah, USA and have unearthed some world-class specimens. They've found Nelumbo leaves over the years but this is their first fossil specimen of the fruit.

And what a specimen it is! The spectacularly preserved fruit measures 6-1/2" round. Here you can see both the part and counterpart in fine detail. Doug Miller of Green River Stone sent copies to me this past summer and a copy to the deeply awesome Kirk Johnson, resident palaeontologist over at the Smithsonian Institute, to confirm the identification.

There is another spectacular specimen from Fossil Butte National Monument. They shared photos of a Nelumbo just yesterday. Nelumbo is a genus of aquatic plants in the order Proteales found living in freshwater ponds. You'll recognize them as the emblem of India, Vietnam and many wellness centres.

|

| Nelumbo Fruit, Green River Formation |

In the older classification systems, it was recognized under the biological order Nymphaeales or Nelumbonales. Nelumbo is currently recognized as the only living genus in Nelumbonaceae, one of several distinctive families in the eudicot order of the Proteales. Its closest living relatives, the (Proteaceae and Platanaceae), are shrubs or trees.

Interestingly, these lovelies can thermoregulate, producing heat. Nelumbo uses the alternative oxidase pathway (AOX) to exchange electrons. Instead of using the typical cytochrome complex pathway most plants use to power mitochondria, they instead use their cyanide-resistant alternative.

This is perhaps to generate a wee bit more scent in their blooms and attract more pollinators. The use of this thermogenic feature would have also allowed thermo-sensitive pollinators to seek out the plants at night and possibly use the cover of darkness to linger and mate.

So they functioned a bit little like a romantic evening meeting spot for lovers and a wee bit like the scent diffuser in your home. This lovely has an old lineage with fossil species in Eurasia and North America going back to the Cretaceous and represented in the Paleogene and Neogene. Photo Two: Doug Miller of Green River Stone Company

Sunday, March 3, 2024

LATE HETTANGIAN FOSSIL FAUNA FROM THE TASEKO LAKES: BRITISH COLUMBIA

This material is very important as it greatly expands our understanding of the fauna and ranges of ammonites currently included in the North American regional ammonite zonation.

I had the very great honour of having the fellow below, Fergusonites hendersonae, a new species of nektonic carnivorous ammonite, named after me by palaeontologist Louse Longridge from the University of British Columbia.

I'd met Louise as an undergrad and was pleased as punch to hear that she would be continuing the research by Dr. Howard Tipper, the authority on this area of the Chilcotins and Haida Gwaii — which he dearly loved.

"Tip" was a renowned Jurassic ammonite palaeontologist and an excellent regional mapper who mapped large areas of the Cordillera. He made significant contributions to Jurassic paleobiogeography and taxonomy in collaboration with Dr. Paul Smith, Head of Earth and Ocean Science at the University of British Columbia.

Tip’s regional mapping within BC has withstood the test of time and for many areas became the regions' base maps for future studies. The scope of Tip’s understanding of Cordilleran geology and Jurassic palaeontology will likely never be matched. He passed away on April 21, 2005. His humour, knowledge and leadership will be sorely missed.

|

| Fergusonites hendersonae |

Both Dan Bowen and John Fam were instrumental in planning those expeditions and each of them benefited greatly from the knowledge of Dr. Howard Tipper.

If not for Tipper's early work in the region, our shared understanding and much of what was accomplished in his last years and after his passing would not have been possible.

Over the course of three field seasons, we endured elevation sickness, rain, snow, grizzly bears and very chilly nights — we were sleeping right next to a glacier at one point — but were rewarded by the enthusiastic crew, helicopter rides — which really cut down the hiking time — excellent specimens including three new species of ammonites, along with a high-spired gastropod and lobster claw that have yet to be written up. This area of the world is wonderful to hike and explore — stunningly beautiful country. We were also blessed with access as the area is closed to all fossil collecting except with a permit.

This fauna understanding helps us to understand the correlations between different areas: (1) the Mineralense and Rursicostatum zones are present in Taseko Lakes and can be readily correlated with contemporaneous strata elsewhere in North America; (2) the Mineralense and Rursicostatum zones of North America are broadly equivalent to the Canadensis Zone and probably the Arcuatum horizon of the South American succession; (3) broad correlations are possible with middle–late Hettangian and earliest Sinemurian taxa in New Zealand; (4) the Mineralense and Rursicostatum zones are broadly equivalent to the circum‐Mediterranean Marmoreum Zone; (5) the Mineralense Zone and the lower to middle portion of the Rursicostatum Zone are probably equivalent to the Complanata Subzone whereas the upper portion of the Rursicostatum Zone may equate to the Depressa Subzone of the north‐west European succession.

|

| Taseko Lake Area, BC |

Since then, knowledge of eastern Pacific Hettangian ammonite faunas has improved considerably.

Detailed systematic studies have been completed on faunas from localities in other areas of BC, Alberta, Alaska, Oregon, Nevada, Mexico and South America (e.g. Guex 1980, 1995; Imlay 1981; Hillebrandt 1981, 1988, 1990, 1994, 2000a–d; Smith and Tipper 1986; Riccardi et al. 1991; Jakobs and Pálfy 1994; Pálfy et al. 1994, 1999; Taylor 1998; Hall et al. 2000; Taylor and Guex 2002; Hall and Pitaru 2004).

These studies have demonstrated that Early Jurassic eastern Pacific ammonites had strong Tethyan affinities as well as a high degree of endemism (Guex 1980, 1995; Taylor et al. 1984; Smith et al. 1988; Jakobs et al. 1994; Pálfy et al. 1994). Frebold’s early studies were also hampered because they were based on small collections, which limited understanding of the diversity of the fauna and variation within populations. However, recent mapping has greatly improved our understanding of the geology of Taseko Lakes (Schiarizza et al. 1997; Smith et al. 1998; Umhoefer and Tipper 1998) and encouraged further collecting that has dramatically increased the size of the sample.

A study of the ammonite fauna from Taseko Lakes is of interest for several reasons. The data are important for increasing the precision of the late Hettangian portion of the North American Zonation.

Owing to the principally Tethyan or endemic nature of Early Jurassic ammonites in the eastern Pacific, a separate zonation for the Hettangian and Sinemurian of the Western Cordillera of North America has been established by Taylor et al. (2001). Except for information available from the early studies by Frebold (1951, 1967), the only Taseko Lakes taxa included in the North American Zonation of Taylor et al. (2001) were species of Angulaticeras studied by Smith and Tipper (2000).

Since then, Longridge et al. (2006) made significant changes to the zonation of the late Hettangian and early Sinemurian based on a detailed study of the Badouxia fauna from Taseko Lakes (Text‐fig. 2). An additional taxonomic study was recently completed on the late Hettangian ammonite Sunrisites (Longridge et al. 2008) and this information has not yet been included within the zonation.

|

| Hettangian Zonation |

The Taseko Lakes fauna can improve Hettangian correlations within North America as well as between North America and the rest of the world.

North‐west European ammonite successions (e.g. Dean et al. 1961; Mouterde and Corna 1997; Page 2003) are considered the primary standard for Early Jurassic biochronology (Callomon 1984).

In north‐west Europe, the turnover from schlotheimiid dominated faunas in the late Hettangian to arietitid dominated faunas in the early Sinemurian was sharp (e.g. Dean et al. 1961; Bloos 1994; Bloos and Page 2002). In other areas, by contrast, these faunas were not so mutually exclusive and the transition was much more gradual.

This makes correlations between north‐west Europe and other areas difficult (e.g. Bloos 1994; Bloos and Page 2000, 2002). Correlations are further impeded by endemism and provincialism.

The Taseko Lakes fauna addresses these problems because it contains many taxa that are common throughout the eastern Pacific as well as several cosmopolitan taxa that make intercontinental correlation possible. Correlation between North America and other areas is of particular significance in that the interbedded volcanic and fossiliferous marine rocks in North America permit the calibration of geochronological and biochronological time scales (Pálfy et al. 1999, 2000).

This correlation between the late Hettangian fauna in the Taseko Lakes area and contemporaneous faunas in other areas of North America, South America, New Zealand, western and eastern Tethys, and north‐west Europe is of particular interest to me — especially the correlation of the faunal sequences of Nevada, USA.

Reference: PaleoDB 157367 M. Clapham GSC C-208992, Section A 09, Castle Pass Angulata - Jurassic 1 - Canada, Longridge et al. (2008)

L. M. Longridge, P. L. Smith, and H. W. Tipper. 2008. Late Hettangian (Early Jurassic) ammonites from Taseko Lakes, British Columbia, Canada. Palaeontology 51:367-404

PaleoDB taxon number: 297415; Cephalopoda - Ammonoidea - Juraphyllitidae; Fergusonites hendersonae Longridge et al. 2008 (ammonite); Average measurements (in mm): shell width 9.88, shell diameter 28.2; Age range: 201.6 to 196.5 Ma. Locality info: British Columbia, Canada (51.1° N, 123.0° W: paleo coordinates 22.1° N, 66.1° W)